Context

Qualitative Research Methods course work

Duration

Two months

My Role

Researcher

Team

Five students

Abstract

We utilized ethnographic and qualitative research methods, including field observations, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups, to investigate people's attitudes, perceptions of safety or danger, and feelings of trust or distrust regarding autonomous public transport, specifically autonomous buses.

We analyzed the resulting data and identified several factors influencing these perceptions.

From these findings, we extracted specific insights and design suggestions aimed at informing the design of future generations of autonomous buses.

Introduction & Problem Statement

If you ask people whether they would get on a self-flying plane, without a pilot, most of them are likely to say no.

Even if you assure them that this imaginary autopilot can fly the plane better than any human pilot ever could, the idea of not having a human at the controls will still leave them feeling a certain level of uneasiness. But why?

That feeling is a good example of what we wanted to investigate in this project, but instead of planes we investigated the phenomenon on buses.

Driverless buses are a new form of autonomous public transport, currently being researched and developed, with a handful of pilot projects out on the road carrying passengers right now. After technical and regulatory issues, we believe that one of the main barriers standing before the widespread adoption of this technology could be the way it is perceived by the public, and in particular its perceived safety.

Keeping in mind that buses are also shared spaces where various social dynamics take place between passengers, our question is the following: How does the substitution of a bus driver in favour of an autonomous driving system, assumed to be reasonably safe and reliable, influence people's attitudes and perceptions of safety towards this mode of transport?

Methods

We aimed to explore the topic broadly while still producing in-depth insights on people’s feelings, behaviors and motivations.

Therefore, we chose to employ ethnographic and qualitative research methods, following a Grounded Theory approach.

We therefore conducted a number of field observations, followed by a series of semi-structured interviews, and a focus group.

1. Field Observations

Twenty-five ethnographic field observations, conducted on and off different kinds of buses (non-autonomous), at various times of the day and night, along different types of routes, and in areas considered to be more or less “safe”.

Observing the bus environment with a critical eye allowed us to gain a good understanding of the wide variety of situations a passenger may find themselves in while while traveling by bus, and how in each of those the perception of safety could be impacted by replacing the human driver with self-driving technology.

A number of observations were also conducted as Online Ethnography, exploring the online discourse surrounding the possible adoption of autonomous buses, especially on social media.

2. Semi-structured Interviews

We then conducted 10 semi-structured interviews, each about one hour long, with a diverse sample of interviewees.

These interviews were based on a guideline formed from the findings of the observations.

We heard many stories, opinions and perspectives that were instrumental for determining specific factors influencing perception of safety, and

it was also interesting to note how these factors changed across different genders or age groups.

3. Focus Group

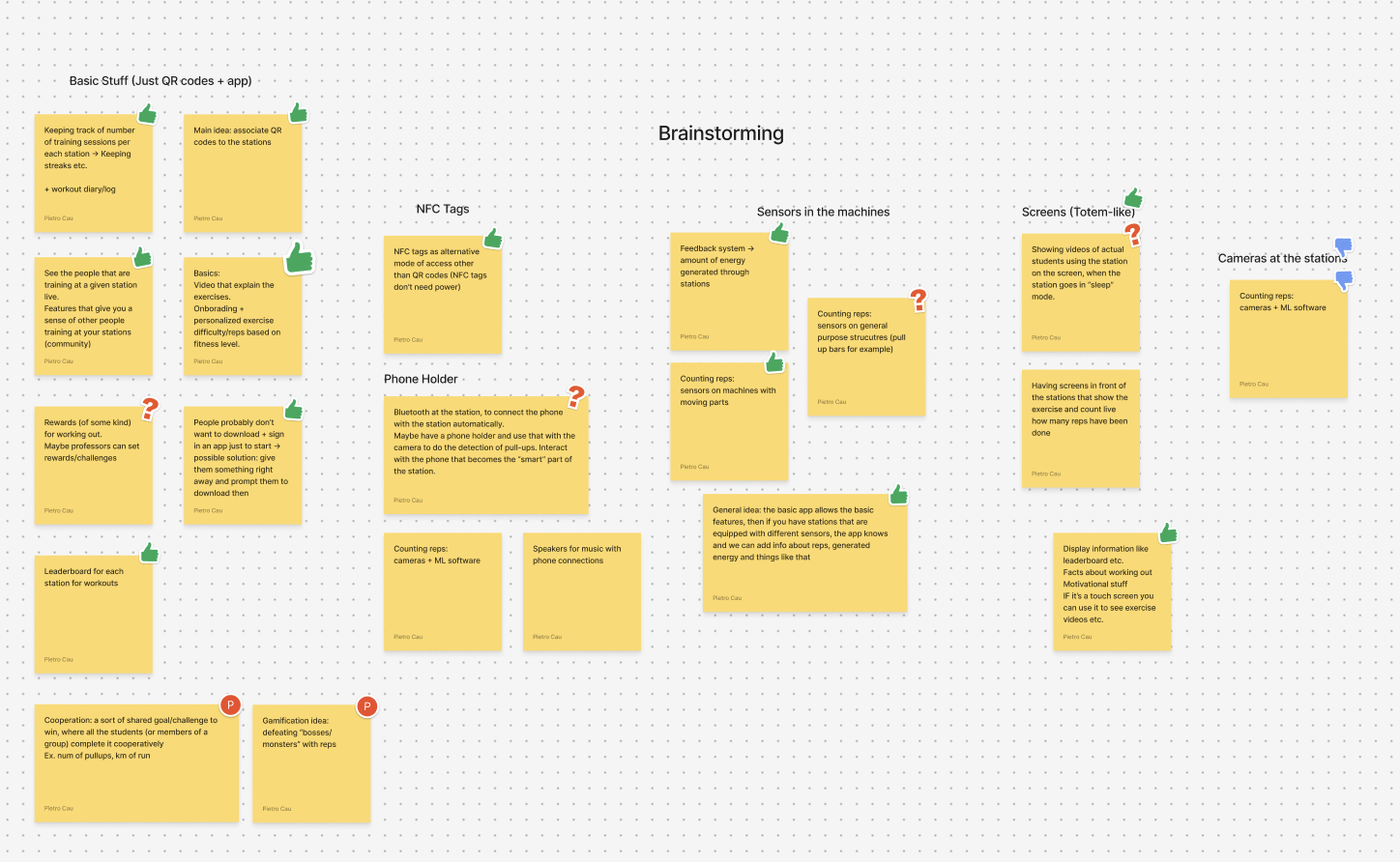

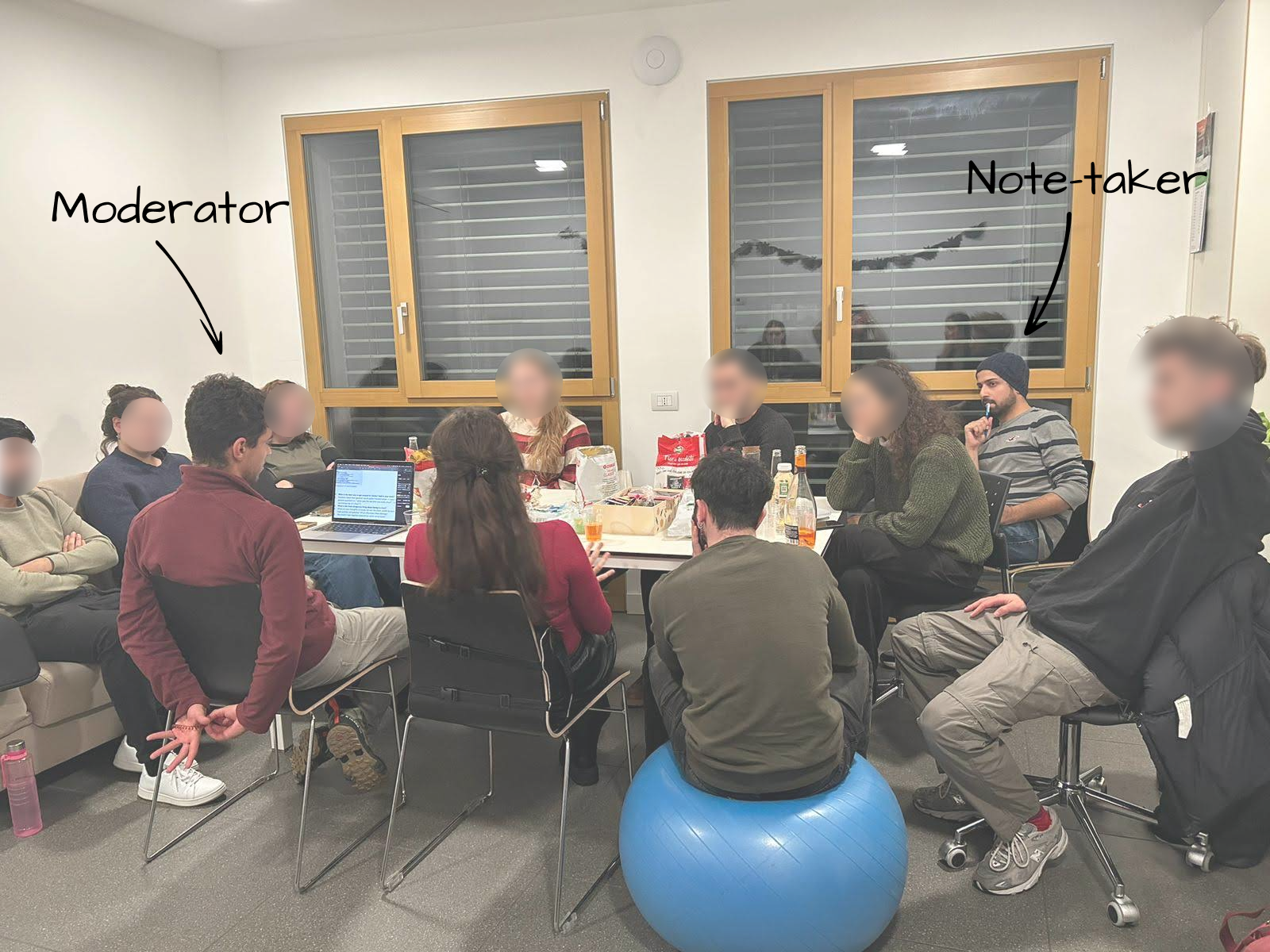

Finally, to further explore the themes raised in the interviews, we conducted a focus group with nine participants, which allowed us to discuss and understand some of the contrasting opinions people have.

Our focus group.

4. Data Analysis

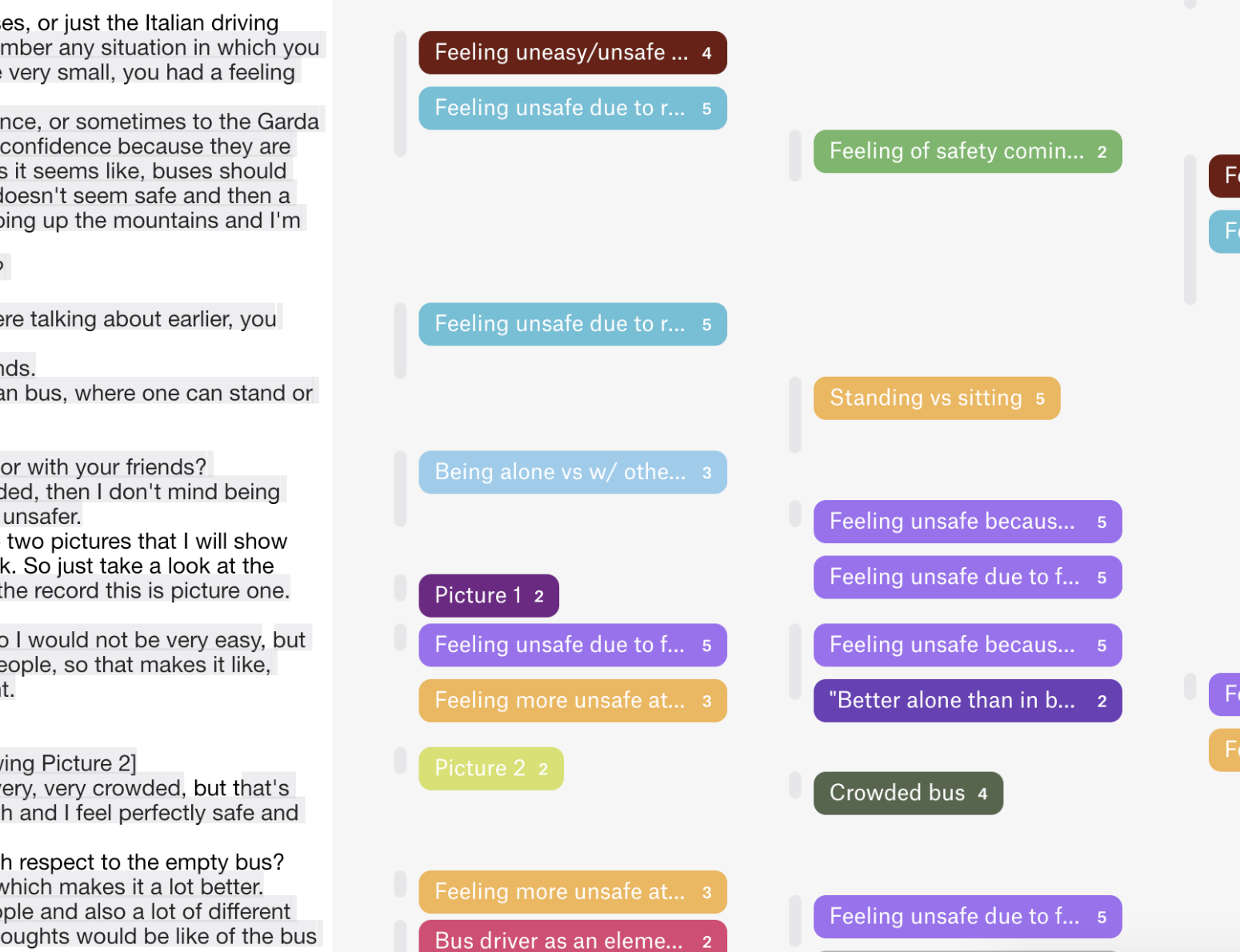

After each step, the resulting documents (field-notes, transcriptions, etc.) were aggregated, and a Thematic Analysis of the data was performed. This analysis allowed us to discover common themes and patterns from which we extracted our findings.

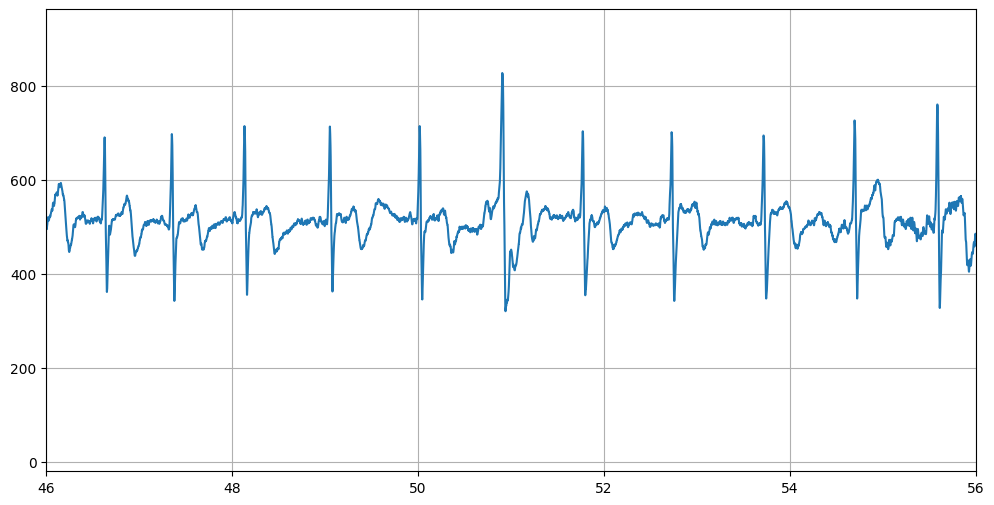

Snippet of Thematic Analysis

Findings

Firstly, we started by categorizing different kinds of fears and concerns.

From the data analysis we were able to identify two macro-categories:

1. "Road Safety" Concerns:

Fear of potential injury that may occur as a consequence of being in a moving vehicle

(e.g. fear of getting into an accident or the fear of loosing one’s balance and falling).

2. "Social Safety" Concerns:

Fear of potential threats that could come from other people on the bus

(e.g. fear of being harassed, robbed or sexually assaulted).

We also found correlations between certain demographic variables (such as gender and age) and the prevalence of one type of concern over the other.

Finally, we identified a total of 19 factors that influence the perception of safety (either positively or negatively), for different kinds of concerns.

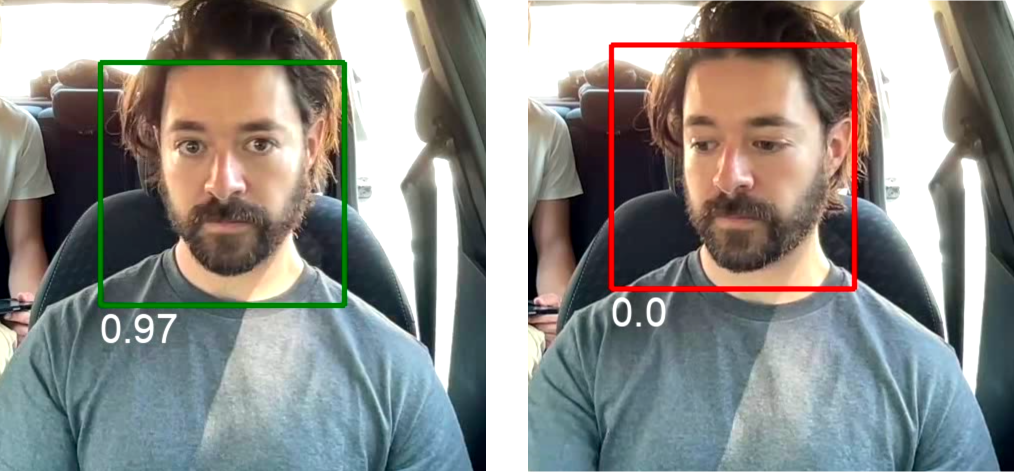

Additionally, although not related to our original research question, it became apparent from our research that bus drivers do much more than just drive, they routinely interact not only with passengers, but also with other road users, mostly in non verbal ways (eye contact with pedestrians crossing the road, hand or head gestures to other drivers when negotiating intersections, etc.). The point being that driving like a human requires a certain amount of social cognition [1],[2].

Actionable Design Suggestions

From our findings, a number of design suggestions and guidelines could be extrapolated, below are some examples:

1. When thinking about a video surveillance system for the interior of the bus, it emerged that the presence of cameras is not enough to provide a sense of safety: what actually made people feel safer were not the cameras themselves, but the idea that someone was actively overlooking the situation, in the absence of this perception, cameras didn’t impact the feeling of safety. Therefore, It may be useful to design systems that not only make the presence of the cameras apparent, but that also convey the fact that there is actually a person actively looking at the video feed.

2. Although not related to safety per se, it was apparent from our research that the bus driver does much more than just drive, he/she interfaces with the passengers, adapts his driving style to their quantity, or positioning within the bus, gives them directions and answers questions, and as mentioned above, also routinely communicates non-verbally with other road users and pedestrians.

Any attempt to design a driverless bus should consider this, and include appropriate features to help retain these important functions.

3. When making interviewees compare images of different buses, the interior lighting of the bus emerged as an important factor in perception of safety, with a badly lit environment being associated with a greater sense of danger. Therefore we believe that the bus interior should be well lit, especially at night. This finding is in accordance with other findings in environmental psychology [3],[4].

And more…

References:

1. Driving in Roundabouts: Why a Different Theory of Expert Cognition in Social Driving Is Needed for Self-driving Cars. - R. Sánchez-García, & D. Araújo

2. The Halting problem: Video analysis of self-driving cars in traffic. - B.A. Brown, M. Broth, & E. Vinkhuyzen

3. Lighting and the Perception of Safety. - N. Bell

4. Feeling Safe in the Dark: Examining the Effect of Entrapment, Lighting Levels, and Gender on Feelings of Safety and Lighting Policy Acceptability. - C. Boomsma, & L. Steg